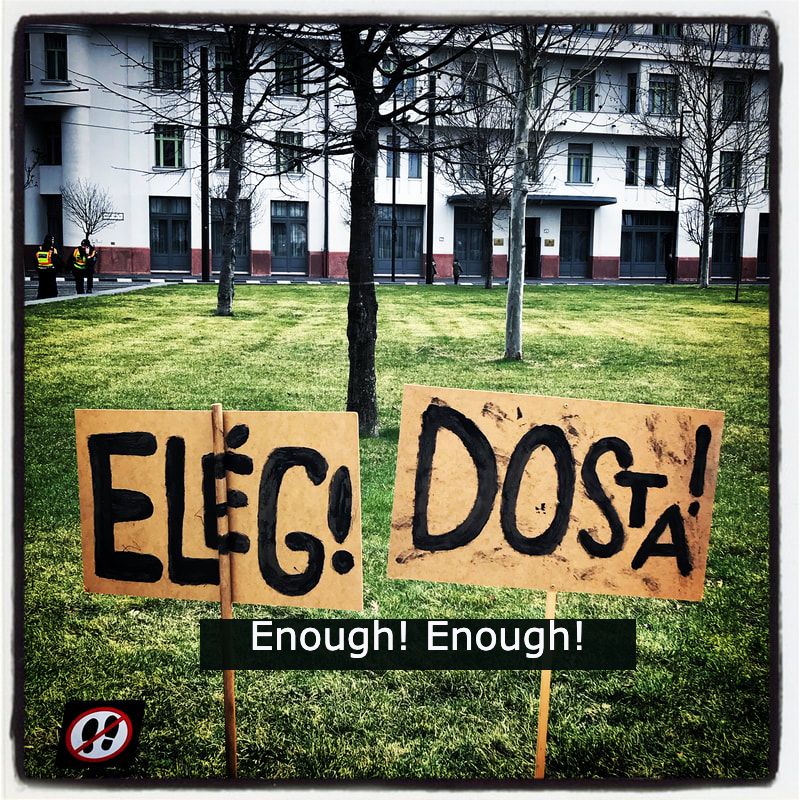

When I was a young girl, living in the Bronx, my parents faced a choice - should I be placed in my school's English only classes or should I be placed in their bilingual program? One quick tour of the classes at that time had convinced my mother that the bilingual classes were not the way to go. They were over crowded, rowdy and clearly were the classes that the problematic students were placed. No, my mother said, she's going to learn English and she is going to learn to speak it well. The idea had been that I would speak English at school and Spanish at home But sadly that never really occurred. Because while I did speak English at school, I also spoke it at home, with my friends, and to my parents - in particular, I spoke English to my mother so she could translate it to my father who only really spoke Spanish (the beginning of a very unhealthy triangulation in our home). But what is a parent to do? Parents often face difficult choices when raising their children, struggling to make sure their children fit in while also wishing for their children to retain their own cultural identity. But, apart from what parents should do, what should the state do? What are the best ways to help immigrant children function in a host country (or as in my own case, what would have been the best way for me, as a citizen, to function in my own country?). Should the state mandate language classes for immigrant children OR should the state institute bilingual, or even, trilingual classes for all? (Before you think that this is not possible - I would like to state that the mean number of languages that my students in Budapest speak is THREE - but that is a post for another day). Should we aim to integrate these children - or are they better served in "catch-up" classes? And catch- up to what? to what norm? to who's standard? Such are some of the questions surrounding the (mis)education of Roma children in Hungary. And I only learned about it because I decided to go for a walk on a rainy Sunday afternoon and walked right into a political protest outside of the Hungarian parliament. Although my Hungarian is quite basic (actually non-existent is more to the point) I was able to make out some key phrases - like antifascists and could also recognize the flag of Amnesty International (because it literally said Amnesty International), and with the help of google translate I quickly understood that this was a rally against the enforced segregation of Roma children in Hungary,. As described in this article from Reuters More than 2,000 Hungarians, including Roma families and civil groups, marched to parliament on Sunday to protest against the government’s refusal to pay compensation to Roma children who had been unlawfully segregated in a school in eastern Hungary. Apparently, in the village of Gyongyospata (in Northern Hungary) there is an ongoing dispute on what should be done after the lower courts declared that the state should pay damages to the families of Roma children who were placed in segregated schools. For almost a decade this has been dragging on with PM Orban suggesting that the state should not pay damages but instead provide "customized education opportunities" instead (see here for further description of this proposal) So what is the role of the state? what obligations does it have toward others? and more pertinently, what are the psychological consequences of pursuing polices that segregate and refusing to compensate when damage has been done? Certainly, there is no shortage of psychological literature pointing to the harmful effects of segregation as the research by Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark showed. In fact, it was their work that showed how racial segregation harmed the self-images of Black children and was formed the basis of decision to desegregate American schools (see here) However, what I would argue, is that segregation does not only hurt immigrant children - but majority children as well. Because segregation prevents contact and limits exposure to others. Segregation also dehumanizes and this was a point I saw echoed in many of the signs at the protest. People also just seemed tired - like really fed up as evidenced by the signs I saw (Enough! Enough!) Of most interest to me is that by the end of that Sunday approximately 500 Hungarian psychologists had signed a petition against this government policy. See psychologists can have a role in shaping social policy. Tags:

1 Comment

Part of the joy of traveling is learning about how things work differently in different places, learning to question our assumptions in order to think differently about the world. Sometimes that learning occurs during the most unexpected and mundane moments - like taking attendance on the first day of class. On my very first day of teaching in Budapest, I had one of those teaching moments when I stumbled into the gender rabbit hole. As part of a get-to-know you assignment, I had students interview each other and ask about basic demographic information, with the idea that they were then to introduce their partners to the class. It was:

It is an assignment I have used countless times in the U.S. with very little difficulty - but that was in the U.S. and not in Hungary. As part of this assignment, I asked students to indicate the pronouns I should use when referring to them. This is standard practice in my U.S. classes and it is a way for me to be sure I am respectful and honoring a student's identity and also a way to signal to other students that this is something that is important to be mindful of. In the past, I have not always been so attentive and have made careless mistakes. I once used to ask about "preferred pronouns" until I had one of students tell me that I should refrain from using the term "preference" because doing so indicated that this reference was somehow optional and not mandatory. That is, it's not who I prefer to be, it is who I am. With that in mind, I made sure to write in my handout that students should inform me as to how I should refer to them and believed doing so would be pretty self-explanatory It was not. Moments into interviewing each other, I could hear students pausing and stumbling when this question arose. Aha! I thought - it is because they do not know the difference between sex and gender - and so this question of pronouns appears odd and different. But that was not the case at all - at least not for this class. Much to my surprise, my students were well-acquainted and versed on the differences between sex and gender, so this was not the reason for the pause. Instead, what was causing the disruption was language. In particular, the language of my informal questionnaire. As I soon came to learn, certain languages can constrict or enable greater gender expression than others and that this flexibility is all a matter of degree For example, while some languages have a pronoun for genders (e.g. think English and it's use of he and hers), and other languages have a pronoun for genders AND objects (e.g. think of my beloved Spanish and its use of el/ella for persons as well as its use of la and el objects - as in la mesa for the table, and el sillón for the rocking chair) - other languages, such as Hungarian (and Estonian and, indeed many more) do not have gender-specific pronouns, and indeed do have a grammatical gender at all. Huh? So, in essence, what this meant is that at least for my Hungarian students, when I asked about their gender pronouns, this question posed a difficulty because they had to think about how they would identify in English. That is, the language of the questionnaire was forcing them to think differently about a concept (which as a psychologist poses a whole host of questions on methodological equivalence). Now to be sure, I am NOT saying that these students had not thought of their gender (clearly many had) they just did not know how they would approach this question - for this class. One consequence of this, as I learned in a wonderful blog post on this: thanks in part to a wonderful blog post on this very issue (see https://deepbaltic.com/2018/03/20/being-non-binary-in-a-language-without-gendered-pronouns-estonian/) is that the lack of gender in these language can enable those who are trans to feel more freedom. HOWEVER, before we all go and drop English and speak Hungarian (which is actually not such a bad idea), it's important to realize that "genderless" languages do not necessarily predict more progressive attitudes toward women and that, in fact, " so-called genderless languages can express societal sexist assumptions linguistically". How? because of a host of sometimes hidden (and not so hidden assumptions). Indeed, speaking a non-genderless language does not necessarily predict pro-feminist attitudes. How do I know that? because in researching this topic I ran across another thoroughly thought-provoking article on gender, language and feminism. and who wrote this article? My landlady Vasvari, Louise. (2011). Grammatical Gender Trouble and Hungarian Gender[lessness]. Part I: Comparative Linguistic Gender. Hungarian Cultural Studies. 4. 10.5195/ahea.2011.40. mind blown. Tags:

Bad choices make good stories. I saw this poster a few days after arriving in Budapest a few weeks ago. It really resonated with me - because I wondered what had I done? How had I left my family for a semester to teach in a foreign country alone, so far from home, with absolutely no grasp of the language? What was I thinking???

This blog is an attempt to catalog my experiences while I am abroad teaching as a Fulbright Scholar in Budapest, Hungary at ELTE. Hopefully I will get to chronicle my mostly good, but undoubtedly, also some difficulty experiences that I am sure to have. Because I have always understood that life is short, I have spent a good part of my life trying to experience as many things as I could. That has sometimes meant making what appears to others to be bad choices, or at least crazy choices, Too often in life woman are told that they can't do things - but that's not always true. This is what this Fulbright is meaning for me - making a crazy (but NOT bad) choice in order to live more deeply and fully - in order to tell good stories, because life is just too short to not live it. Tags:

|

AuthorFulbright Scholar in Budapest, Hungary.. ArchivesCategoriesPesky DisclaimerFriends .- this is NOT an official Department of State website or blog, and the views and information presented are my own and do not represent the Fulbright Program of the U.S. Department of State. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed